Is plasma the cause?

The physics of crop formations

By John A. Burke

Editor’s Note: Last month Nancy Talbott discussed some of the specific analyses of physical trace cases conducted by the BLT research team of John Burke, W. C. Levengood, and Talbott, as well as possible links between crop circles, UFOs, and animal mutilation cases. This month Burke discusses the force he feels may be involved in creating the crop circles.

In 1989 the

appearance of two books on crop circles, combined with some media coverage,

alerted most Americans for the first time to the appearance of a previously

unrecognized phenomena which had no precedent: large, geometric-shaped areas of

crop which had been flattened overnight.

Writing a letter

to author Pat Delgado to ask for details on the biological studies, career

biophysicist W. C. Levengood was shocked to find that no biological studies

were being conducted. He asked for and received plant samples taken in line with

his instructions in what was to become a steady stream of plants across the

Atlantic. As formations were reported in the U.S. and other countries, samples

were obtained from them as well—always with control samples taken from

unaffected parts of the same field for comparison. Today, after meticulously

analyzing tissue samples from five countries and more than 300 formations involving many types of crops,

some clear patterns have emerged.

Whatever the

force which makes crop formations, it physically alters the tissue of the

flattened plants in a number of ways. Over time an hypothesis has emerged

suggesting plasma as the active force. None of the following effects has

occurred when formations have been made (by us and others) using all the

techniques claimed by those who have “confessed” to hoaxing the crop

formations:

1. Stalks which

are very often bent up to ninety degrees without being broken, particularly at

the nodes, which are like the joints of wheat stems. Something softened the

plant tissue at the moment of flattening. This is particularly dramatic in

canola (rapeseed), which otherwise is as stiff as celery at this stage of

development.

2. Stalks which

are usually enlarged, stretched from the inside out by something which seems to

heat the nodes from the inside. Sometimes this effect is so powerful, the node

literally explodes from the inside out, blowing holes in the node walls and

spewing sap outside the stalk. This has been measured in thousands of samples to

a degree of 95% to 99% probability

(“significant” to “highly significant,” in the language of science).

Levengood has duplicated this effect using microwaves.

3. Stalks which

are left with surface electric charge. We have measured this in two formations

which were only a few hours old. The degree to which the stalks were bent over

was proportional to the degree of electric charge on the stalk, strongly

suggesting the force which pushed it over was electrical.

4. The thin

bract tissue surrounding wheat seed which has had its electrical conductivity

increased, consistent with exposure to an electrical charge.

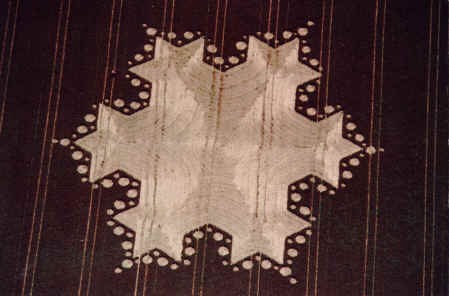

This formation was discovered near Silbury Hill, Wiltshire, England, in a wheat field in July of 1997. It features a border of 126 small circles and a width of 350 feet. (Photo by Steve Alexander)

Natural causes?

As scientists we

had to next ask if there is anything in nature which shares these

characteristics. The answer is yes—plasma. Plasma here is simply electrified

air. It carries electric charge, and when it travels through a magnetic field

(like the geomagnetic field which exists everywhere on the planet) it does two

things:

1.) It moves in

a spiral, the most common pattern in which crop is flattened.

2.) When it spirals thus it emits microwaves.

This is the same principle used in your microwave oven, where electrons are spun

around a magnet in the roof and emit the microwaves which penetrate the tissue

and heat from the inside by interacting with the water in the food. The nodes,

the most affected part of crop formation samples, are the site with most of the

plant’s water.

Plasma was first

hypothesized as the cause of crop formations by English meteorologist Terence

Meaden. He suggested the plasma was in the form of a vortex produced

meteorologically. Unfortunately crop formations did not seem overly dependent on

any set of weather conditions, and the model did not explain non-circular

formations.

We asked

ourselves, was there any other possible source for plasma? Lightning is an

example of a very powerful, very high energy plasma. It is caused by plasma

(electrically charged air) far above ground in thunderheads up to eight miles

high being attracted to opposite charges in the ground. But lightning is a much

higher energy plasma than that which makes crop circles (where no charring

occurs).

The ionosphere,

on the other hand, is a region of low energy plasma 40-80 miles up in our

atmosphere, where most of the air is electrified by solar wind and cosmic rays.

The only time that some of this plasma gets energetic enough to glow is when we

see the Northern Lights. It was long believed that the ionosphere and the

earth’s surface were completely separate, and that never the twain would meet.

In recent years, decades of airline pilot sightings were confirmed with

scientists’ photos of electrical flashes in the air between thunderheads (8

miles high) and the ionosphere (up to 100 miles high). The several types of

these have been dubbed “sprites.” These are apparently very common events. So

there are frequent exchanges of electric cargo between the ionosphere and a

storm 90 percent of the way to the earth’s surface.

We believe that

sometimes the exchange may cover the other 10 percent of the distance as well

and actually reach the ground. Something similar is known to happen every night

everywhere when plasma penetrates part way down (causing perturbations in the

geomagnetic field). Normally these attempted penetrations are bounced back the

way they came by the reflective layers of the ionosphere. These are the same

reflective layers which AM radio waves bounce off to communicate over the

horizon. At night these layers weaken and rise (which is why you can get AM

radio reception much further away late at night).

They are weakest

in the predawn hours, when most crop formations occur. The ability of plasma to

penetrate these reflective layers is directly proportional to its “vorticity”;

i.e. the tighter and faster spinning the plasma cloud, the further it can

penetrate toward the ground. The “magnetic pinch” effect insures that as such a

plasmoid descends toward the surface, it shrinks in size and spins faster (much

like spinning figure skaters accelerate by pulling in their arms).

An increase in “ammunition”

The amount of “ammunition” in the

ionosphere, in the form of free electrons, increases up to 100 times between

sunspot maximum and sunspot minimum. Crop formation frequency, at least in

England, has roughly paralleled sunspot numbers. The huge outbreaks of

1988-1989 coincided with the most powerful sunspot maximum in their 170 years of

recorded history, and have declined accordingly since. This roughly eleven-year

cycle should peak again near the millennium.

The meteoritic connection

The strongest evidence for the ionosphere as

the origin of crop formation plasma comes from microscopic particles of

meteoritic dust found in 2/3 of the 32 formations where we have been able to

obtain soil samples. The heaviest concentration ever was found in 1993 in an

English formation which appeared on the night of the largest meteor shower to

hit Europe in 30 years. This example became the basis of the second paper we

have have managed to publish on crop circles in a peer-reviewed paper (Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol.

9, pp. 191-199, 1995).

Sub-millimeter-sized bubbles of pure iron oxide (magnetite) coated

both the ground and the crop in that formation. To summarize a detailed and

technical investigation, the material was identical to the debris which erodes

from meteors as they burn up in the atmosphere, and which takes 7-10 days to

settle to the ground. It can be picked up with a magnet (as could some of the

wheat in which it had become imbedded). It has since appeared in the majority of

formations from 13 states and 5 countries where soil samples were obtained.

Inside formations, it appears in 20 to 100 times the normal concentration for

soil.

As plasma

spirals around geomagnetic field lines it creates its own magnetic field. This

would tend to attract and carry along any magnetite dust particles encountered

as it descended from the ionosphere. The ubiquitous presence of this material

has essentially ruled out a low altitude source for the plasma.

Established scientific facts

These are

extremely well-established and long-established scientific facts. Nothing said

so far is remotely controversial, except for the idea of plasma reaching the

ground from the ionosphere. Plasma loves to organize itself into spirals. Most

aurora are actually arrays of tight tubes of plasma vortices seen from the side

as they spin around the geomagnetic field lines. One third of all aurora

organize themselves into gross spirals as well. One candidate—the small

curl—seems a likely candidate for crop circle formation. It is often as small as

400 meters across where it starts in the ionosphere, but shrinks as it

descends.

Plasma might, we

reasoned, be reaching the wheat fields of England from the ionosphere, but why

did so many occur in one small area of England—and how did they form some of

those incredible patterns? These are two very distinct issues. In a search for

why

any plasma might be

particularly attracted to one tiny area 30 miles or so across, we eventually

looked at hydro-geological maps of England and found something remarkable.

Crop formations in England overwhelmingly appear over

shallowly-buried parts of a giant chalk aquifer. England has the world’s deepest

chalk aquifer. (The white cliffs of Dover are a view of one side of it.) They

also have some of the world’s greatest seasonal fluctuations of water levels—up

to 100 feet. Was there anything about this which might attract plasma? As it

turned out, there was. Water percolating through porous rock—any kind of porous

rock—creates electric charge. This occurs by a process called “adsorption,”

where electrons are stripped off water droplets as they move through rock pores,

leaving a net negative electric charge behind on the rock and a net positive

charge on the water which drains

through.

This "sine/co-sine" formation was discovered at East field, near Alton Barnes, Wiltshire, England, in June of 1996. It features 89 circles and a length of 648 feet. (Photo by Steve Alexander)

With calcium carbonate (the mineral which makes up chalk)

there is a chemical process when the water dissolves some of the mineral, which

further reinforces this same charge separation. Wherever charge separation

Occurs in a body which can conduct electricity, electric current flows and

generates its own magnetic fields. We measured these ground currents and their

changing magnetic fields in 1993 at Silbury Hill, long the center of the most

intense crop formation activity in the world.

Crop formations

in southern England overwhelmingly occur where this electrically-charged

rock is closest to the surface. The largest formations and most frequent

formations happen late in the summer when the aquifer is most run down, and the

most water has therefore run through the most rock. The beginning of the modem

phenomenon of large, spectacular formations begins in the late seventies and

early eighties, a time when over-pumping for public water supplies began to

lower the water table noticeably. Droughts have coincided with banner years for

crop formations.

In England, our

team has measured the kind of magnetic fields one would expect to accompany such

electric ground currents in one field that has nearly annual formations. Four

days later a major formation occurred there. Follow-up fluxgate magnetometer

measurements four days after this sixty-foot dumbbell formation appeared showed

that the magnetic readings and the currents which produced them had vanished.

This is not unlike the discharge with that more powerful plasma—lightning. In

that case ground current attracts the airborne plasma, and when the plasma (the

bolt) hits the surface it neutralizes the ground current.

Limestone is the

chemical twin of chalk. It too is calcium carbonate, but much less porous than

chalk. It too has the ability to generate ground currents from interaction with

water, but not nearly so much as chalk. Thus it is fascinating to note that

limestone aquifers are the major exception to crop formations occurring over

chalk substrata. Formations in England do happen a minority of the time on the

large limestone aquifers there.

In the U.S. we

have no substantial chalk deposits, but huge stretches of limestone aquifers: in

Florida, on the Eastern Coastal Plain, throughout much of the Midwest, and

virtually all of the Great Plains, extending into Canada. Finally a thin stretch

runs down the West Coast. These locations are where crop formations occur. As in

England, the most active sites seem to frequently be where an edge of the

aquifer occurs or where a river valley has cut through the aquifer to produce an

edge. Proximity to water is also typical (no surprise considering the current

generated between water and the rock it ran through).

Shape most difficult to

explain

This leaves us with the question of shape—the

most difficult aspect to explain with a natural model of crop formations. The

most common patterns in the crops are the most common patterns seen in plasma in

the laboratory. It is important to remember that plasma is scale invariant;

anything which happens on a scale of inches can and will happen on a scale of

miles, etc. So it is worth noting that plasma in the lab most commonly organizes

itself into a spiral—the most common pattern of flattened crop. Next most common

in plasma is the swirled disc surrounded by concentric rings (the “bulls-eye” or

“target” pattern). This is also the next most common in the fields. Furthermore,

in both mediums the concentric rings tend to alternately swirl clockwise

and counterclockwise as you move out from the center (or in from the

edge).

Other patterns

Other patterns seen in plasma and crops include floral

patterns, nested crescents, dumbbells, and others. The hardest to understand

using the plasma model, are straight lines and right angle shapes. It is

counterintuitive to think that air can form such patterns. However, as

electrified air, plasma behaves more like an electromagnetic fluid (and so the

physics of plasma motion is “magnetohydrodynamics”) While it is also contrary to

common sense that liquids form such shapes, in fact they do—when excited.

American physicists exciting liquids with sound waves have produced surface

ripple patterns that include squares, triangles, hexagons, and others. We must

remember that a crop formation is the two-dimensional record of the passing of a

likely three dimensional shape. The ground (2D) is likely to record only a 2D

slice of a 3D plasmoid. So even 2D patterns in the plasma could got recorded on

the ground.

Deterministic

chaos is a new branch of science which has repeatedly shown that systems which

are excited or turbulent can assume surprisingly geometric patterns. Ilya

Prigogine received the Nobel Prize for showing that 2D geometric patterns often

form of their own accord in 3D pools of liquid chemical reagents.

A ball of plasma

being drawn ground-ward by an electromagnetic hot spot is likely a turbulent

system. As such we can expect that patterns will spontaneously arise, however

briefly. If that is the moment at which the plasma impacts the ground. that is

the pattern we can expect to appear in the crop. However, with plasma there is a

positive feedback loop which might tend to refine certain patterns until they

are of the picture-perfect sort we so often encounter.

Certain shapes

called waveguides will attract plasma likes bees to honey. A rectangle is one

such shape and is a primary reason why ball lightning (a high energy plasma)

loves to enter houses through the chimney. Chimneys are rectangular tunnels.

Another commonly-used waveguide in industry is the dumbbell shape (which

happens frequently in the fields.) Still another is the “key” or “F’ shape we

often see attached to circles (called the Millman Waveguide).

Plasmas create

their own magnetic field lines. If, by random chance, the magnetic field in a

turbulent plasma takes on a waveguide shape, it could create a positive feedback

loop. More plasma will be attracted to that part of the plasma ball, vortex, or

cloud which has assumed that shape. The plasma will spiral along those magnetic

field lines as it moves. When plasma spirals around a magnetic field line it

strengthens that field line, which can now in turn attract more plasma, etc.

Thus this shape might tend to get “locked in” and even refined until close to

its ideal shape. At the moment this is a highly speculative but stimulating

hypothesis. It still strains the imagination to think how some of the more

elaborate patterns might arise from sheer plasma physics.

One aspect of all this that has long bothered

us was that if this is a natural phenomenon, then it should frequently not come

out geometric at all. Nature does not always get everything perfect. As it turns

out, we now believe that most plasma impacts result in non-geometric flattening

of the crop. Of course, crops around the world are constantly being flattened by

non-plasma events like wind. However, sometimes close inspection of such ragged

downed areas reveals the same bent nodes as in formations. Sometimes a large

field which gets flattened in a non-descript pattern will have within it

small areas of spiraled lay and other lay patterns (with 180 degree opposition)

impossible if wind was the cause.

Same tissue

changes

Sampling and lab

analysis of many such sites has shown a great number to have the same tissue

changes as in formations. In fact the most dramatic node changes ever recorded

have been in such ragged downed areas—including nodes which were blown apart

from the internal pressure. This is in keeping with plasma physics. Plasma will

spontaneously organize itself into a vortex shape—if the energy level of the

plasma does not get too high. When the energy level exceeds a certain threshold,

the plasma’s ability to maintain the vortex pattern breaks down. Examination of

photos of crop formations very often shows such ragged areas of downed crop all

around the formation. Our pattern-seeking minds, however, ignore this, and we go

straight to the geometric formation, considering this to be the only “genuine”

event in the field.

We believe that

plasma, in whatever shape, is probably impacting the ground far more often than

we realize. We have analyzed rings in grass which have undergone physical

changes consistent with plasma contact. If plasma were to hit streets or

buildings it would leave no visible record. A series of concentric rings found

in sand on a beach showed very high levels of ionization. A circle in dirt in a

Colorado field had some of the highest concentrations of meteoritic dust we have

ever seen—only in the top three inches of ground and only inside the

circle.

Like sprites?

We believe that

the plasma we are studying may turn out to be like sprites. Their existence,

reported for decades by airline pilots, was ignored by science until a

professional scientist took photographs of them. Now that scientists are

looking, they are discovering sprites to be incredibly common wherever there are

thunderstorms. We have one daytime photo which looks like a small plasma vortex,

and the rare eyewitness accounts of circle formation are consistent with our

model. Likely one day everyone will know of such events. In the meantime we have

those amazing patterns to admire and puzzle over.

BOX 400127

CAMBRIDGE, MA

02140

phone:

617/492-0415